Asylum artist Sophia Sobko recounts the transformations of the social roles she inhabits as a queer, post-Soviet, Jewish immigrant, the importance of finding allies to articulate these positions and the potential for action such communities hold. Sophia and Kolektiv Goluboy Vagon are now celebrating the launch of their first publication, a samizdat (zine) composed of 76 color pages of art and writing from their members.

We have always been looking for one another, even when we didn’t know to try.

This feels like the most apt way to describe Kolektiv Goluboy Vagon, a group of gender-marginalized, queer and trans, white post-Soviet diasporic Jews that has been convening virtually over the last eight months. The group was born of my love and anger, and of the desire to pursue a radical politic of co-liberation from a grounded and historicized place: as white, as Jewish, as post-Soviet, as queer, as gender-marginalized, as immigrant/settler in the U.S. Meeting twice a month on Zoom long before the rest of the world was forced to, we have formed relationships, drank chai, interrogated power structures, addressed ancestral trauma, created ritual, shared art and writing, developed a mutual aid system in response to COVID-19, and most recently hosted a public reading and performance. We are now celebrating the launch of our first publication, a samizdat (zine) composed of 76 pages of art and writing from our 20+ members.

While I’ve likely been dreaming up this project my whole life, I trace its origins to 2016, when, just rounding 30, I unexpectedly came into my queerness. It was a time as terrifying and destabilizing as it was thrilling and expansive. This first “coming in” was quickly followed by a second one: a curiosity about my Jewishness, and more specifically, my Russian and post-Soviet immigrant Jewishness. Though I had been doing justice-oriented work in the U.S. for a decade and had developed a critical analysis of whiteness and white supremacy, these new explorations exploded how I understood my own artistic and political efforts in the world.

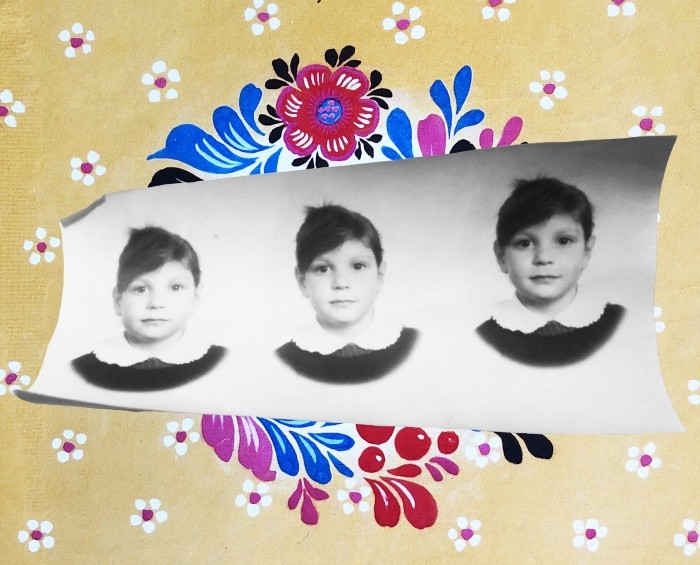

Image credit: Irina Zadov, Sophia Sobko, Audrey Berman (krivoykolektiv.com)

For many years I had been working as a social practice artist and educator, facilitating the cultural production and self-representation of others. Still, regardless of how participatory my methods were, all of this work saw me in a leadership role over people of color and undocumented people. As I rooted into my own history and identity, I began to deconstruct the ways I had been socialized into saviorist roles as a white woman in the U.S. I turned my gaze away from racialized people of color, toward structures of power and my own complicity in them. This tectonic shift offered me the space to feel into a more authentic driver of my work: the pain and madness of emigrating from a place where my family was ethnically oppressed, only to be assimilated into a system that protects me at the expense of others. I felt into what “co- liberation” meant for me, realizing that my own humanity was at stake.

In these years I paused my social practice work and instead took time to learn and to ask myself where I ground, knowing that that soil nurtures the direction and impact of the work I do in the world. Soon enough I felt the familiar tug of participatory practice. I yearned to explore my questions with others who shared my immigration history, life experiences, and positionality – both the dominant/complicit and marginalized parts. At that point, I was not sure that they actually existed.

Artwork: Irina Zadov | submission to the samizdat/zine

In some ways, my people found me. In 2018 I came across an Instagram Queer Personals ad posted by Stepha Velednitsky, who was searching for lefty queer post-Soviet Jews. This led me to find the Facebook groups “Anti-Trump Soviet Immigrants” (Olga Tomchin, 2015) and “the soviet jews r queer”, created by Rivka Yeker in 2017. Leveraging my resources as a PhD student, I shifted my research topic to post-Soviet Jewish diasporic whiteness and began dreaming up an online group study and participatory art studio where I could work with my community on our complicity, pains, healing, and potential to contribute to co-liberation.

Eight months later, as our internal work becomes more public, the kolektiv is working to articulate our values with integrity and specificity. Many of us are driven by a shared conviction: our family members did not suffer anti-Semitism and state violence in Russia and the Soviet Union for us to now benefit from the oppression of others. As the project founder, I have many dreams for us- to move toward collective leadership, to continue artistic and cultural production, to develop accountability to impacted groups including U.S.-based post-Soviet Jews of color, and to begin forming coalitions with other immigrants resisting assimilation and envisioning co-liberation. Already, many in the kolektiv have stepped into leadership roles, co-facilitating sessions, visioning and problematizing, and organizing our first public-facing event. With the launch of our zine, 28 current members, and 7 applications still to process, it feels like we are just getting started.

Visit www.kolektivgoluboyvagon.com or email kolektivgoluboyvagon@gmail.com to get in touch!