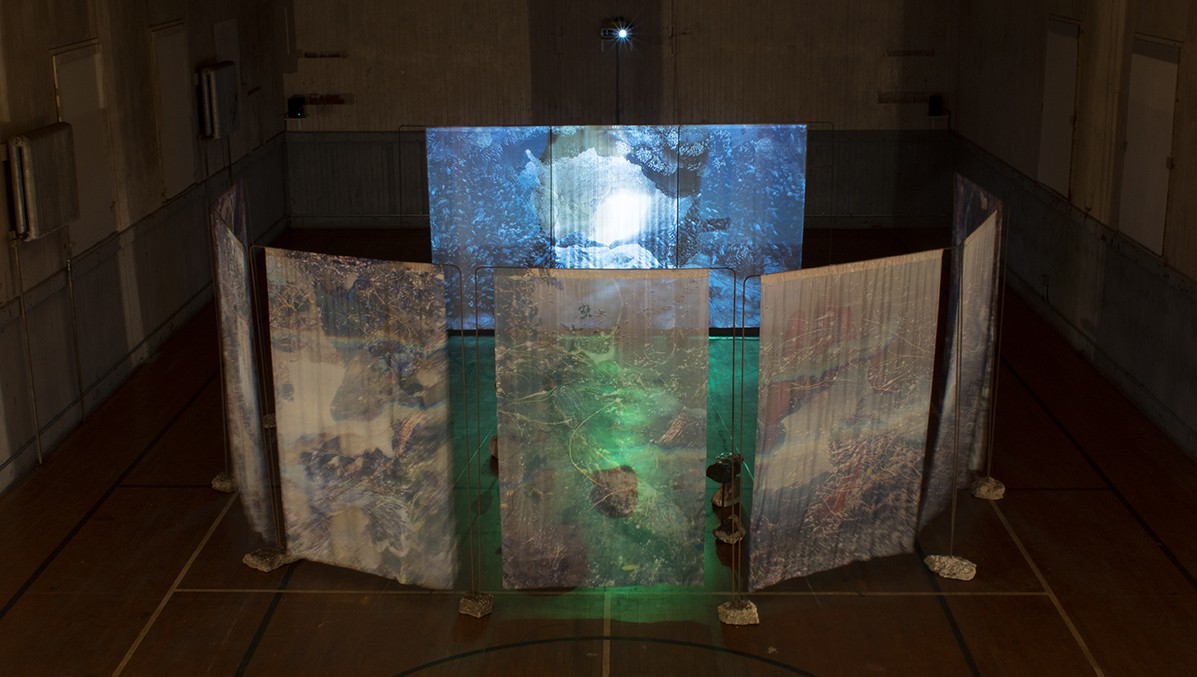

We Become [Vessels] was a three part video and sound based installation created by Annie Albagli at Headlands Center for the Arts’ Gym between May 14-23, 2021 and supported by Asylum Arts small grants. The Shofar, or ram’s horn, is a tool from Jewish tradition to mark the new moon and new year, and is said to have toppled the walls of Jericho. Pairing the Shofar with rocks inviting human touch, video, sound, and silk flags featuring composite images of the Headlands landscape, Albagli’s installation in The Headlands Center for the Arts’ Gym proposes new ways to move through space and time. Framed by the Marin Headlands and its history, We Become [Vessels] instigates movement between place, people, and generations, using ancestral tools for the exploration of the threshold of the self, our interdependence, and speculative imaginings.

In this interview, Annie speaks with Curator, Amanda Nudelman to expand on the themes of rituals, repetitions and collaborations, and how these can be used to build meaningful connections between one another and the environments we inhabit.

Amanda Nudelman: Annie, your video installation We Become [Vessels] includes a number of formal elements—a video projection, a number of free standing sculptures made from rock and concrete, richly printed silk banners—and just as many themes and subjects that we could explore in our conversation. But sadly, I don’t think we’re going to have time to address everything. Instead, I’m planning to pull on just a few threads of thought throughout our discussion. So let’s dive in! From the moment you enter the installation, and then especially after watching the three-part film, it’s clear that this work is a response to the Marin Headlands—both its landscape and history. But you’ve also woven a number of outside lines of research through this narrative and the exhibition environment you’ve created. How did this work come about and what was your approach to bringing these different elements together?

Annie Albagli: Yes, the work is a coalescing of many strains of research and is absolutely a response to the site of the Marin Headlands. When walking through the Headlands landscape, one encounters an abundance of military infrastructure built throughout and into the hillsides, including concrete bunkers, Nike Missile sites, radar and launch control centers, etc. The extent to which the military altered the landscape makes itself clear in elusive and jarring ways as you walk around—iceplants subtly reveal hidden concrete forms or bunkers abruptly jutt out. As I worked onsite, surrounded and provoked by these structures built to protect the nation state, I became increasingly curious about the origins of nationalism and its formation.

Benedict Anderson addresses what he considers to be the catalyzing force of nationalism’s rise throughout the first European nation states in his book Imagined Communities. He theorizes that, beginning in the 17th century, the newspaper standardized and flattened language to allow seemingly disparate citizens access to shared information, fostering synchronicity and connection among its readers. Today, rather than reading a single newspaper, innumerable media streams facilitate semiotic concatenations with little shared meaning—what Franco Berrardi calls, “governing through chaos.” Said another way, mass media deepens societal fissures and exhausts our mutual understanding. This feeling was especially potent while researching these topics throughout 2020.

As an antidote to the divisive chaos and artificiality of the imagined community, I turned to theorists like Emanuele Coccia, who explores the connection between the human and non human. In Coccia’s newest book, The Life of Plants, the Metaphysics of Mixture, he posits a world where plants and animals, through the production of air and circulation of breath, both contain and are contained in our shared atmosphere. He depicts our interdependence through this fundamental act, our shared breath, that moves through and around humans, plants, and animals. This prompted me to ask, how can we change our perception of the self as beyond the body, rather than relying on superficial forms of connection? Can these changes build stronger reverence for our fellow humans and nonhumans?

Lastly, throughout this initial period of investigation, I participated remotely in the diasporic schools hosted by Kunstenfestivaldesarts in Belgium with the artist Yael Bartana. We met throughout the fall to study and learn to play the shofar. Embracing this tool from my cultural history and background, and thinking about it in relation to this landscape and shared breath, brought many threads together through the enunciation of a specific sound.

Amanda: Continuing this line of thought about containers and what we contain (vessels!), can you tell me about where the title of the work came from?

Annie: The title comes from a conversation between myself and artist Robyn Awend. We were paired together for an exhibition and shared a conversation over zoom in February. She often works with language in her practice and I asked her if there was a word that came to mind in relation to letting go or holding on that rises to the surface for her. She mentioned that when talking through day to day life with friends and family, she finds herself asking, How is your capacity level? What are you holding for? Is something expanding for you? She went on to say, we become vessels for everything… micro and macro, constantly shifting between the two. Throughout the pandemic, we are expanding and retracting to accommodate the needs and urgencies of the moment. As I developed this work, I thought about bodies, rocks, and place as vessels and what each of these holds. We Become [Vessels] felt like a potent framing of this work, an entry point that situates the project both within the idea of the container and the contained as well as this specific moment.

Amanda: Circling back to the shofar, sound and voice play an active and important role in the work and I’d love to talk more about how the score, recorded natural sounds, and the voiceover contribute to the overall soundscape of the work. The shofar, which is the instrument made from a ram’s horn that you play in the film, makes a singular and striking sound. Each time I hear it play in the work, I have the strange experience of my body seeming to become both totally still and also fully activated. I’m wondering how your body feels when you play it, and what its significance is in the work?

Annie: That is such a wonderful reflection, Amanda, and your description of the stillness and full activation echoes how I feel when I play it and hear the resulting sound.

The sound of the shofar is used to mark many cycles and rhythms. In Jewish tradition, it marked the new moon, the new year, the final moments of Yom Kippur, made the walls of Jericho fall, and in some commentaries it connects to the idea of stopping cycles of violence. I used the shofar and it’s sound to invoke previous generations, relationships to war, and acts of compassion. Additionally, this work recontextualizes the shofar’s ability to topple walls—like in the story of Jericho. Unlike the story of Jericho, in this work, the shofar sounded from inside a country facing out. It proposes using this instrument as a tool to disintegrate boundaries, rather than lay claim to territory.

To return to the sound emitted from the shofar though—playing the shofar in the Headlands revealed to me a whole new way to experience the landscape. At the start, I felt hesitant to emit a loud sound that connotes many things (alarms, horns, etc.) in shared public space and, as a result, only played it inside the studio. When I did play it outside for the first time, I went to one of my favorite secret spots in the Headlands and sounded it into these arches that enclose tide pools only accessible during low tide. As the sound erupted, I realized how the crashing waves and rock, sea bells, fog horns, and wind build a cacophonous landscape. Then, when it subsided, the chaos of the landscape relaxed and a deep quietness entered. In this calm, the distant calls of the fog horns and sea bells, sounds that respond to present weather conditions, resumed as though in answer to my call.

One visitor to the exhibition described this experience of the shofar as almost like a bat’s echolocation; you send out a sound and a mapped landscape is returned to you through sound and vibration. The shofar’s call provided a new way to experience a place, one I came to realize I previously only understood visually and not sonically. This mapping of sound marks the present so clearly within a landscape constantly in flux from erosion and moving tectonic plates.

Amanda: We’d be remiss in not talking more about the sonic aspects of the work. Its beautiful score and the narrative of the voiceover both felt transportive to me, especially working in unison. Who wrote the music and how did you develop its ethereal quality?

Annie: The score was composed and edited by musician, composer, and sound engineer, Joshua Quarles. The score combined field recordings I collected from the Headlands and the narration that I recorded, with the music and sound that Josh created. Through an ongoing series of exchanges, we talked about how the manipulation of the sound’s spatial qualities could invoke other sites and moments in time as well as how some of the music can morph into other sounds such as the shofar. Our conversations also covered different feelings to evoke as it pertained to different elements that the video focused on, such as the wind, rocks, or sea. I feel honored to work with Josh who makes new spaces possible within the work through sound.

Amanda: There’s a moment in the voiceover when you shift from describing some of the components of the Headlands landscape—like the basalt rocks—and turn your attention toward the viewer. You say, “Do you long to brush against your mother again? To return to a certain sea? Do you miss the top of a specific hill? Or the road you take to get there? These rock bodies can take you there.” These questions were the point when I felt truly implicated and immersed in the work. Before this you take great pains to create a lush environment through image and detailed textual description, and it ultimately feels like it’s all a setup for these transportive phrases. Now, my body, my home, and my family are drawn into the piece, and in my mind I immediately drop into this world you’ve created. The final line, a statement rather than a question, roots me in the physical elements of the installation, and also acts as an invitation to tap into the space-time continuum contained with the rocks!

And this brings me to another observation and another question for you. I feel like you further gesture to this experience I’ve just described of “going home” in your repetition of the word “return,” bringing to mind cycles of time and exchange. Can you speak more about your intention there?

Annie: Thank you for seeing and hearing this! Your question is a reminder of how fortunate I feel when someone brings forward new observations in a work! There are many relationships to the word “return” in We Become [Vessels]. First, it connects to cycles of time, like when the shofar is played in the new month and the new year. It also references the changing seasons particular to this site and the way pebbles cycle through and consistently return on this pocket beach. In addition, the shofar itself is formed in the shape of a spiral, so the object always returns to itself, but slightly misaligned at a higher elevation.

The repetition of the word “return” centers the body, and focuses on the act of coming back to ourselves, the answers we hold, or a place that encapsulates a part of us. At one point, the narrator states, I return to what we hold and what holds us, the breath, to retrieve the answer. Ultimately, in this work, it is the breath that unlocks these portals in the body and bridges connections between space and time.

Amanda: It’s funny that you should talk about the breath unlocking portals. Before we sat down for this conversation, I had just watched your film again and then started reading an interview with another artist called Woody de Othello, who described some objects they were working on as “hope omens.” But I misread it as “hope opens.” The phrase seemed to connect directly back to We Become [Vessels]—in particular, the more speculative last third of the film—bringing some poetic language to an aspect of your work I had been mulling over, but hadn’t been able to articulate for myself. In trying to challenge your own feelings of alienation prompted by the military bunkers, you create what I might describe as an opening for hope in this uneasy relationship. What prompted your new thinking, and how did you go about building intimacy between you and these military structures?

Annie: This is such a beautiful phrase and misreading, Amanda, and captures a lot of intention behind my approach to this work.

For context, at the end of 2019 I completed two multi year projects that were heavily reliant on the archive. It was then that I started reading some of Rosi Braidotti’s writing and also looking back to other writers and theorists whose work addresses hope. I felt exhausted by this constant sense of apocalyptic malaise and wanted to think imaginatively and speculatively, rather than only turning to, drawing from, and retelling the archive as a way to contextualize a present day issue.

When I began researching the Headlands, I focused on the bunkers, while also reading Coccia’s writing about our interconnection through breath and atmosphere. These two strains of research coalesced when I came to understand that Radiolarian Chert, which composes the geology of the Headlands, comes from small skeletal bodies that ooze and over time harden to become rock. A new intimacy was born as I came to understand the materiality of these bunkers. Their concrete holds the evolution of living bodies, which at one time were goopy and now millions of years later help fortify borders. It’s towards the end of the film that I use the shofar and breath to awaken the softness of the past imbued in these constructions. By being of the past and connecting to past generations, could the call of the shofar also awaken the memories of a wall’s material origin? The call transforms these structures into portals to softness, materials that can trespass through barriers such as breath, water, air, and light.

Amanda: That’s really beautiful Annie. I wanted to end by asking about your intentions for the work. In an effort to squeeze all the juice from the phrase, and at the risk of sounding glib, can you talk about where “hope opens” in this work? And whether you think of the phrase as a proposal or an invitation?

Annie: This work is definitely an out loud processing of a site I initially felt alienated from. It addresses both the history of a place and tries to find an entry point through a personal cultural connection. By implicating myself and proposing new imaginaries publically, I hope the work will act as an invitation for others to find a new vantage point to reimagine their relationship with a landscape and its history. Most importantly, however, this outloud processing encourages us to ask how speculative thinking changes how we view our interconnection and interdependence, and if it will influence our decisions in the future?

To me hope opens through the visual portals created in this work, the questions they instigate and the research they require to envision them; they help me see that the boundary of myself extends far beyond my physical body. Hope opens through the intimacy created through understanding the materiality of the Headlands landscape, in using tools from my ancestors, and in finding ways to reimagine structures that remind me of a violent history. During the exhibition, my friend shared that it takes one thousand years for 1mm of chert to form. There’s nothing like thinking about your lifespan in relation to Deep Time to contextualize a human life in the grand scheme of the universe—and that opens great hope.

This interview took place in preparation for a talk at the Headlands Center for the Arts’ Gym in Marin, CA, on the unceded ancestral land of the coast Miwok people. The conversation invited the public into continued insights and conversations Annie and Amanda exchanged throughout a few months leading up to the exhibition.

About Amanda Nudelman: is a curator based in San Francisco. She is currently Curator for North America Programs and Video & Exhibitions Manager at KADIST San Francisco, and has staged exhibitions at The Wattis Institute, swissnex San Francisco, and a screening program at Royal Nonesuch Gallery, where she and Annie first met. She earned a master’s degree in Curatorial Practice from California College of the Arts.

About Annie Albagli: Through sound and video based installations, socially activated sculpture, print, and community engaged projects she explores personal narratives and their entanglements with ecological histories and landscapes shaped by power in order to build meaningful connections between one another and the environments we inhabit. Her work has been shown nationally and internationally at such venues including YBCA, the Corcoran Gallery of Art, and the Art Museum of the America, and the Headlands Center for the Arts. Between 2017-18, Albagli was a YBCA Truth Fellow. She is a co-founder and editor of the publication, WHIZ WORLD, and is currently an Affiliate Artist in residence at the Headlands Center for the Arts.